The 1972-73 New England Whalers

The remarkable story of the WHA's first championship team

This article was written for inclusion in the Society for International Hockey Research's (www.SIHRHockey.org) 50th Anniversary of the WHA publication.

Some portions of the on-line version are not included in the printed version simply due to space limitations.

Enjoy the read - All feedback welcome!

Frosty

The Birth of the New England Whalers

For most 28-year-old businessmen with empty bank accounts, the thought of owning a professional sports team would simply be a distant dream. However, when Harold Baldwin and his partner John Coburn

picked up a copy of The Boston Globe in June of 1971 and learned the World Hockey Association (WHA) was forming, they knew they needed to be part of it.

Despite his young age, Baldwin was no stranger to hockey management. At the time he saw the article in The Globe, Baldwin, along with Coburn, was in the process of trying to develop a new ice arena

in the greater Cape Cod area with the hopes of it being a home base for a new Eastern Hockey League team.

While growing up in New York, Baldwin played hockey, including serving as captain for the Salisbury School (Salisbury, Connecticut) team in 1961. After a short stint in the United States Marine

Corps, Baldwin attended Boston University (BU) in the fall of 1962. It was there that he met first-year hockey coach Jack Kelley and the freshmen team coach Bob Crocker.

Coach Crocker cut Baldwin from the BU freshmen hockey team, as his time with the Marines had left him a bit rusty on the ice. Not to be deterred, Howard would return the next season for another go

at trying to make the Terriers squad. This time around, Baldwin recalls, “Coach Kelley told me that he was not going to cut me, but I knew I wouldn’t see much ice time. With my interests in playing

hockey starting to change, I opted to step away from the game as a player.” While Baldwin’s time spent with Kelley was short, the coach left him with a lasting impression as a strong disciplinarian,

a fair coach, and a good guy.

Shortly after leaving college hockey, Baldwin stepped away from BU to try his hand at a professional baseball career in Florida. Unfortunately, that never materialized, and it lead to him working

at a sporting goods company in New York City.

Then, at a chance meeting with family friend Bill Putnam, who would later become an executive vice president for Jack Kent Cooke, Baldwin landed an operations manager role with the Jersey Devils

of the Eastern Hockey League for the 1966-67 season. This is where Baldwin got his first real hands-on experience running a professional hockey team. The NHL’s expansion for the 1967-68 season

provided an opportunity for Baldwin to join the Philadelphia Flyers front-office staff, working alongside Ed Snider. His initial role was as the team’s ticket manager and then later as the team’s

sales manager.

In November 1970, after three-plus seasons with the Flyers, Baldwin wanted to explore other opportunities. He packed his car and headed north to Marion, Massachusetts, where he met friend and

future business associate Coburn who was busy running his family’s clothing store. After seeing the WHA story in The Boston Globe, Baldwin and Coburn pivoted from their desires to build an arena

to landing a WHA franchise.

With high expectations, Baldwin and Coburn reached out to WHA founders Gary Davidson, Don Regan, and Dennis Murphy to discuss joining the new professional hockey league. The WHA leadership group

desperately wanted a franchise in the Boston area, so they were quick to schedule a meeting with the Massachusetts businessmen.

For Baldwin and Coburn, this presented the first of many challenges. For starters, they didn’t have an office. But they quickly found a small space in Marion. Next, they needed furniture. So,

they worked with family friend Al Ford, who just happened to own an antique store, to outfit the office prior to the meeting. In exchange for his help with the furniture, Ford was given 1%

ownership in their potential WHA team.

The first meeting in the makeshift office went well. So well, in fact, that Baldwin and Coburn were invited to the first official WHA league meeting in October 1971. It was held at the Americana

Hotel in New York City. During this meeting, potential team owners learned that the league’s entry fee would be $25,000 plus an additional $10,000 to cover league dues.

Despite leaving this meeting without a signed deal, Baldwin and Coburn were optimistic. They started working on the logistics of where the team would play home games, who would help them build

the roster, and, most importantly, who was going to pay for everything. While this searching for answers was ongoing, the league’s second official meeting was scheduled at the Fontainebleau Hotel

in Miami in November of 1971.

During Baldwin and Coburn’s travels to Miami, they started chatting with Boston-area executive Phil David Fine. Fine had been instrumental in the development and construction of Schaffer Stadium,

the Foxboro, Massachusetts home of the National Football League’s New England Patriots. Fine also had connections with law offices that represented the Boston Bruins. Upon hearing of the duo’s

plan to secure a WHA franchise, Fine told Baldwin and Coburn to contact him when they returned home and he would help them find an arena. Of course, that was assuming they got a team.

At the Miami meeting, WHA officials reinforced their desire for a New England-based team to be part of the league and expressed support for Baldwin and Coburn. However, league officials threw a

major hurdle to all potential new team owners as they increased the league franchise fee from $25,000 to $250,000.

Caught up in the moment, and not to be deterred, Baldwin and Coburn signed the necessary paperwork. They also agreed to find the league’s entry fee, a place to play their home games, and a general

manager to help assemble their team before the next official league meeting. They had three months and a lot of work to do before heading to Quebec City in February 1972.

The top priority, upon returning from Miami, was finding an investment partner that could finance the team. Bob Schmertz, a real-estate developer from New Jersey that was part owner of the NBA’s

Portland Trailblazers, and actively trying to land a Canadian Football League franchise to play in Yankee Stadium, was identified as a potential investor. Baldwin and Coburn met with Schmertz in

December 1971 to pitch their plan and, in one meeting, were able to finalize a deal that provided the group with financial stability and funds to begin building the new franchise.

Now the focus turned to hiring someone to assemble the roster. In January 1971, Baldwin and Coburn discussed the combined general manager/head coaching role with two individuals; former Boston Bruins

coach Harry Sinden and BU’s Jack Kelley. Sinden, who had left the Bruins after the 1970 Stanley Cup championship because of a dispute over his salary, had expressed some initial interest but backed

out after learning he may have an opportunity to coach Team Canada in the upcoming Summit Series against the Soviet Union. The focus then turned exclusively to Kelley. In the years since crossing

paths with Baldwin in 1962, Kelley had built BU into a perennial college hockey powerhouse, winning the NCAA championship in 1971. While Kelley was up for the challenge and very interested in the

chance to coach the new professional team, he wanted a guaranteed paycheck if he stepped away from BU. Schmertz guaranteed Kelley’s three-year deal worth $30,000 per year and the team officially

signed its general manager and coach on January 24, 1972. Howard recently said, “Even if Harry Sinden had said he was interested in the job, we may still very well have hired Jack.”

Jack Kelley and his BU Terriers celebrate a Beanpot championship in 1967

(courtesy of BU Sports)

Jack Kelley celebrates another BU hockey victory

(courtesy of BU Sports)

In late January 1972, Kelley still had obligations to BU and continued coaching the Terriers. He also started to assemble his supporting staff and targeted many members of his BU team including

Rob Ryan (assistant coach), Bob Crocker (player personnel), and Jack Ferreira (former BU goalie).

In addition to announcing Kelley as coach on January 24, 1972, the ownership group also announced that the team had a name, The New England Whalers. The name “Whalers” was Ginny Kelley’s idea.

Ginny was Jack’s wife and thought that whaling represented a big part of the region’s heritage. The decision to go with New England instead of Boston was due to a large boat manufacturer already

having the name Boston Whalers.

With Schmertz, Kelley, and the team’s name now firmly in place, the focused turned to figuring out exactly where the Whalers would call home. The first choice for an arena was the newly constructed

Providence Civic Center. However, the Civic Center Authority’s loyalty to the Rhode Island Reds, combined with the ownership group’s inherent corrupt activities, took that option off the table. When

Baldwin and Coburn returned home from the second league meeting in Miami, they had reached out to Phil David Fine to let him know that they were granted a franchise. Now it was time to see if Fine

really could work his magic. Fine delivered by landing the new franchise a rather well-known home arena, The Boston Garden. In return for his assistance, Fine asked that the new team allow his firm

to represent the team for any future legal matters.

Whalers Executive Team: Bill Barnes (Exec VP), John Coburn (Exec VP), Howard Baldwin (Pres.), and Godfrey Wood (VP)

(courtesy of Tom Frost Collection)

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, there was no better Hockey Town in the world than Boston. Spurred by the arrival of a blonde-haired kid from Parry Sound, Ontario, the Boston Bruins took the city

and NHL by storm. In a period of six years, Bobby Orr and the Big, Bad Bruins went from being perennial NHL doormats to two-time Stanley Cup Champions (1970 & 1972). And, if not for a pair of bad

knees and the play of a rookie goalie in a Habs’ sweater named Dryden, chances are that they could have won a few more titles. Some hockey fans also point to the arrival of the WHA for helping to end

what may have been a 1970s Bruins dynasty.

While landing at the Garden was a dream for Whalers’ ownership, the Adams family owned the Garden, as well as the Boston Bruins, and were not very fond of the new hockey league. Thus, it did not make

things easy for the new franchise. In addition to the Bruins, the American Hockey League’s Boston Braves and the National Basketball Association’s Boston Celtics called the Garden home. Additionally,

events such as the circus, boxing, and concerts limited available dates, so Baldwin still had to find a secondary arena to host some of the team’s home games. As such, Baldwin began making arrangements

to call the Boston Bruins original 1924 home across town, the Boston Arena, the Whalers secondary venue after arena management there agreed to complete some major renovations to the old hockey barn on

Massachusetts Avenue.

The third WHA league meeting took place in Quebec City, as scheduled, in early February 1972. During it, Schmertz was introduced to the WHA brass and announced his presence by saying, “We are excited

to be part of this new league, but we are not paying a $250,000 franchise fee. We will pay the same $25,000 franchise fees the other teams have paid.”

And, just like that, the New England Whalers officially joined the WHA.

On February 12-13, the WHA held its first player draft in Newport Beach, California. With assistant coach Ron Ryan, Baldwin, and Coburn in attendance, as well as Kelley on the phone, the Whalers began

to start to piece together their team. At this point, the draft was used to give WHA teams exclusive negotiating rights with selected players. There was no guarantee that the players would sign with

any WHA teams, as most of the players selected were active NHL and AHL players.

The WHA Draft: Ron Ryan (on phone with Jack Kelley in Boston), Howard Baldwin, and John Coburn

(courtesy of Howard Baldwin)

For Kelley and his staff, the approach was one of being realistic as they selected players that they believed had a good chance of signing with them. They looked for players with ties to New England.

Additionally, with Kelley’s college hockey experience, they also looked to sign former college players, historically ignored by NHL teams. They also opted to stay away from any of the big-name stars

and, instead, focused on character guys that they felt they could build a solid team around.

Time would show that the New England Whalers were very successful at the draft as they signed many of the players selected including Larry Pleau, Rick Ley, Tom Webster, Tim Sheehy, John Cunniff, Brad

Selwood, Tommy Williams, Bruce Landon, and Al Smith.

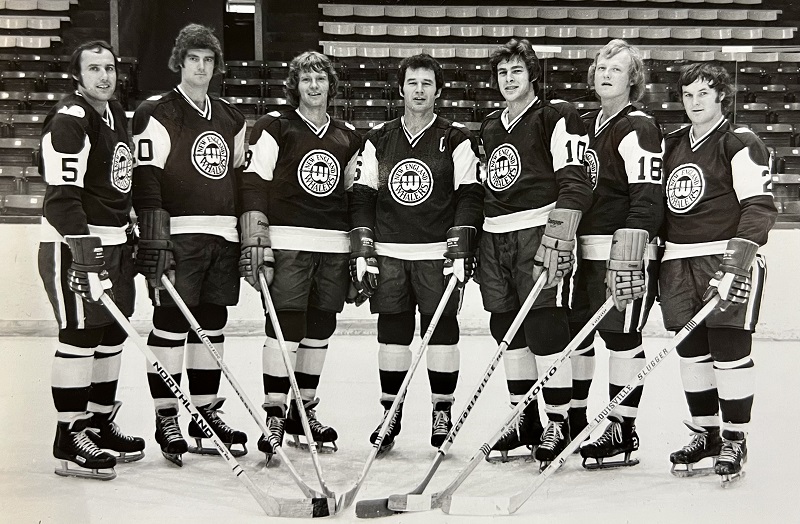

The Whaler's American-born Players (L to R): Kevin Ahearn, Tommy WIlliams, Tim Sheehy, Larry Pleau, Paul Hurley, John Cunniff, Don Cahoon

(courtesy of Tom Frost Collection)

While other WHA teams had begun signing players shortly after the draft (Bernie Parent was the first major player to sign with WHA when he inked a deal with the Miami Screaming Eagles on Feb 27, 1972),

Kelley focused on coaching his Terriers hockey squad and would joyfully go out on top, leading the boys to their second straight NCAA national championship.

Following the completion of the BU season, Kelley and team began to assemble the Whalers roster, starting with inking their first player, Larry Pleau, on April 19, 1972.

Jack Kelley and Howard Baldwin with Larry Pleau as he signs with the Whalers

(courtesy of Howard Baldwin)

Pleau was a local boy that grew up in Lynn, Mass. and had made the unconventional jump to Canadian juniors as a youngster when he joined the Montreal Junior Canadiens. At the time, it was almost

unheard of for a US-born player to head to Canada and play junior hockey, as opposed to playing high school and college. Following his successful career in juniors, Pleau skated for Team USA at the

1968 Olympics in Grenoble, Switzerland before staring for the Jersey Devils of the EHL during the 1968-69 season, earning Rookie of the Year honors.

Over the next three seasons, Pleau would spend time in the Montreal Canadiens system, bouncing back and forth between the parent club and their AHL farm team, the Nova Scotia Voyagers.

When he was first approached by the Whalers to gauge interest, Pleau went to Canadiens GM Sam Pollack to discuss the deal. Pollack scoffed at the idea of Pleau leaving the Canadiens and joining the

rebel league stating, “It will never happen and, if you do sign with that league, you will never play in the NHL again!” However, when Larry learned that his Whalers three-year contract for

$30K/$40K/$50K/year was guaranteed, as compared to his two-way deal with the Habs for $15K/year, he decided to forgo the bleu, blanc et rouge of Les Habitants for the green and white of the Whalers.

Other signings would soon follow including a hattrick of defensemen; Brad Selwood, Rick Ley and Jim Dorey from Toronto, and young forward from Team USA and Boston College named Tim Sheehy.

The first goalie the team would sign was AHLer Bruce Landon. Landon had just wrapped up his third season in the AHL playing for the Springfield Kings and was coming off a Calder Cup Championship season,

splitting time in net with Billy Smith. Following the conclusion of the playoffs, Landon found himself being claimed by the Montreal Canadiens in the league’s reversal draft. Realizing he was not at the

top of the team’s NHL goaltending depth chart with the likes of Ken Dryden ahead of him and having established roots in the Springfield area, Landon was more than happy to sign with the Whalers when he

signed a two-year deal for $25,000/year – a significant increase over the Habs’ offer of $9,500/year.

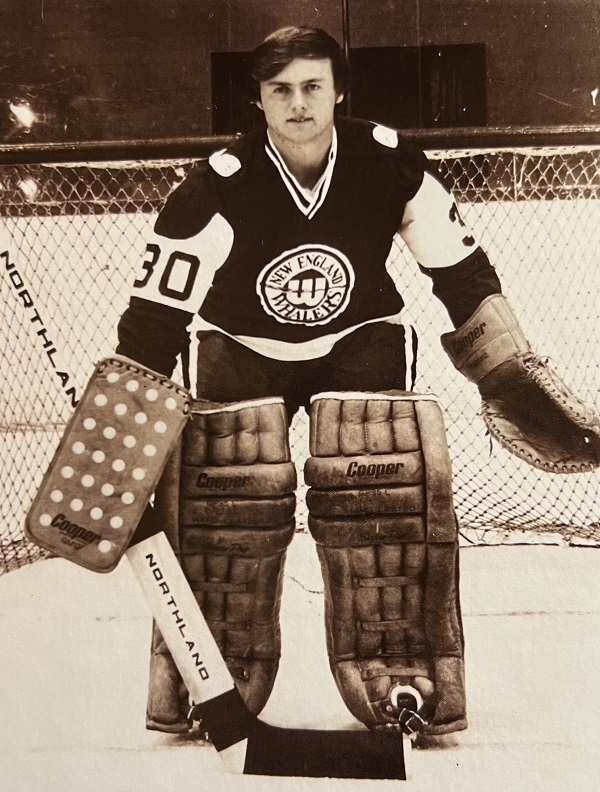

Bruce Landon

(courtesy of Bruce Landon)

While the Whalers brass were assembling their team, one WHA team made front page news all across Canada in July when the Winnipeg Jets signed NHL All-Star Bobby Hull to a record contract with a $1 million signing bonus. This deal provided the WHA with a much-needed shot of legitimacy, so much so that each WHA team agreed to contribute $100,000 to the bonus (note: per Howard Baldwin, only four teams actually contributed any money to the deal: New England, Cleveland, Quebec and Winnipeg).

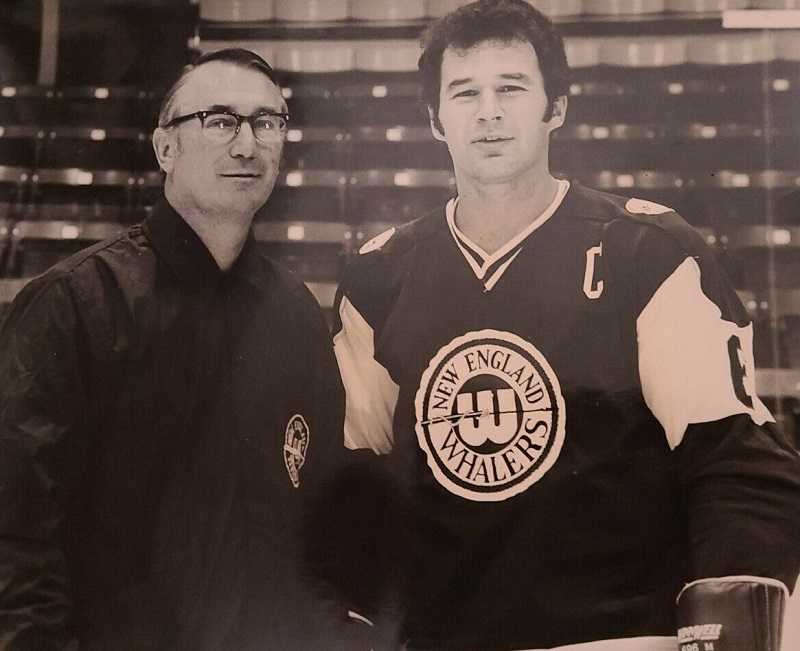

Howard Baldwin, Bobby Hull and Jack Kelley

(courtesy of Tom Frost Collection)

Following the Hull signing, other marquee NHLers would sign contracts with the league including three prominent Boston Bruins: Gerry Cheevers, Derek Sanderson, and John McKenzie.

On July 27, 1972, the Whalers would make their biggest splash when they signed a former Boston Bruin of their own, Ted Green, to a $60,000/year contract and immediately named him the team’s

first captain.

Ted Green

(courtesy of Tom Frost Collection)

Green had been claimed by his hometown Winnipeg Jets in the league’s entry draft back in February but had negotiated his own release, so that he could keep his family in the Boston area and play

for the Whalers.

Green had been a regular member of the Boston Bruins since the 1961-62 season and had built a reputation of a “tough, hard-nosed defenseman”, earning him the nickname of Terrible Teddy Green with

the “Terrible” referring to how opponents felt about playing against him. However, Green’s life and career took a major turn during the 1969-70 exhibition season, when he was involved in a

stick-swinging incident with the St. Louis Blues’ Wayne Maki that left him with a crushed skull and clinging to his life.

Jack Kelley and Ted Green

(courtesy of Tom Frost Collection)

Despite missing the entire 1969-70 season, Green would eventually recover from those injuries, with the help of several metal plates being inserted in his skull, and rejoined the Black and Gold

playing in all 78 games during the 1970-71 season.

During the 1971-72 season, a slightly less physical and slower moving Ted Green fell out of favor with some Bruins fans that would have preferred that some guy named Orr be on the ice for 60 minutes

every game. He would also see a much more limited roll with the team than he was used to. The situation got to the point where Green actually wanted nothing to do with the team’s celebration when

the Bruins captured the 1972 Stanley Cup championship with a victory in the finals over the New York Rangers.

For Kelley, Green represented a solid NHL player with valuable experience and a lot to prove. Time would show that Kelley chose wisely as Green was a well-respected captain and leader of the Green

and White in the three seasons he played for New England. Additionally, by adding Green, the Whalers now had a team defense with over 19 years of NHL experience on the blueline.

New England Whalers defense (L to R): Paul Hurley, Ric Jordan, Brad Selwood, Ted Green, Jim Dorey, Bob Brown, Rick Ley

(courtesy of Tom Frost Collection)

As the summer of ’72 was beginning to wind down, the Whalers added another important piece when they signed Al Smith to play goalie alongside the capable Bruce Landon. In Smith, the Whalers had

landed a dependable goalie with valuable NHL experience.

“Al was an absolute battler that hated to lose”, explained Bruce Landon. “He was an ultimate competitor and was always very supportive when it was my chance in net”, he added.

Al Smith

(courtesy of Tom Frost Collection)

Before the summer would end, the Whalers roster would include a few more forwards with NHL experience including Tom Webster and Tommy Williams.

Webster had missed most of the 1971-72 season due to an injury with the California Golden Seals but had shown great promise with the Detroit Red Wings, scoring 30 goals and recording 37 assists

during the 1970-71 season. He reported to the Whalers that he was “healthy and felt great” when he signed and would go on to have a remarkable six-year career with the Whalers.

For Tommy Williams, it was a home-coming of sorts. Nicknamed “Bomber”, Williams was a former Boston Bruin that, at one time, was the only US-born player in the NHL. The former 1960 US Olympian

and gold medal winner had played eight seasons with the Bruins before being traded to the Minnesota North Stars prior to the 1969-70 season. After several seasons in Minnesota and several more

in California, he found his way back to Boston during the 1971-72 season, albeit as a member of the Boston Braves, the Bruins AHL affiliate.

As the calendar flipped to September, the team’s roster was looking solid and the start of the Whalers’ first training camp would arrive. The camp was held at Boston University and was lightly

attended at first as any players that had been under contract for the 1971-72 season were unable to skate due to legal issues. To start the camp, there were only eight first year pros that had

been drafted in attendance along with 25 amateur free agents. During the summer, the NHL had filed an injunction against the WHA in an attempt to prevent them from “stealing their players”.

However, when October arrived, the WHA had won their battle against the NHL in court and the remaining 16 players under contract with the Whalers could finally hit the ice. With only 11 days before

the regular season was to begin, Kelley worked the team very hard as he was a no-nonsense coach that demanded an honest effort and wanted to have the boys ready.

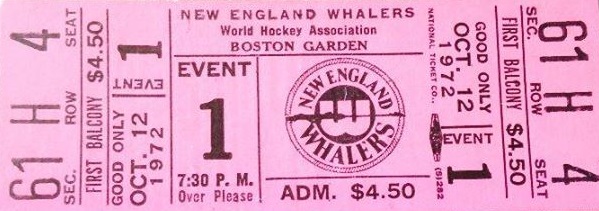

New England Whalers Opening Game Ticket

(courtesy of Mark Rankin)

On October 12, 1972, a sold-out crowd of 14,552 fans packed the Boston Garden for the Whalers home debut against the Philadelphia Blazers and watch this new team with the harpooned “W” crest do

battle against some former Bruins fan favorites: Derek Sanderson, John McKenzie and goalie Bernie Parent.

Philadelphia opened the scoring on a goal by Derek Sanderson 6:32 into first period and would add another goal six minutes later. Just over a minute later, at 13:42 of the first period, Tommy

Williams broke in on a breakaway and wristed a shot high glove side by Bernie Parent to record the first goal in Whalers’ history.

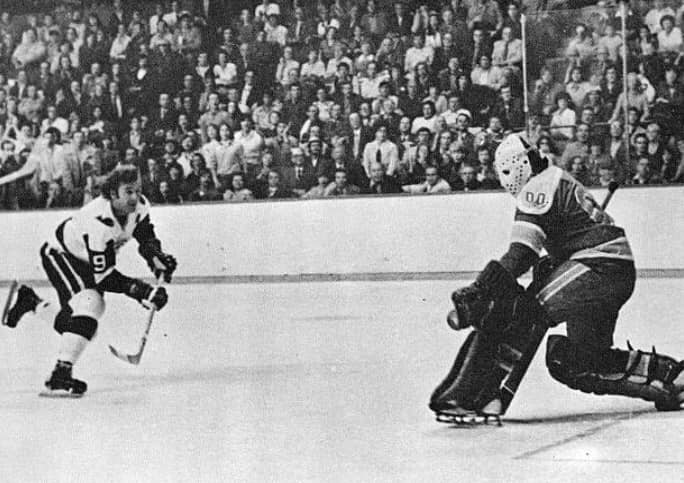

Tommy Williams scores the first Whalers goal vs. Bernie Parent

(courtesy of Tom Frost Collection)

The teams were knotted in a 3-3 tie until Larry Pleau netted the game winner with 2:11 remaining in the game to give the Whalers their first WHA victory.

“The crowd was electric! It was very exciting and it was a special feeling knowing that what we had set out to do was actually happening” said Baldwin. “The Boston fans welcomed us as if we had

been playing in front of them for years.”

“That first game was special. It was a sign that it was all very real. Scoring the winning goal was just icing on the cake” shared Larry Pleau. “All we wanted as players was more money and

more ice time. The WHA change hockey forever.”

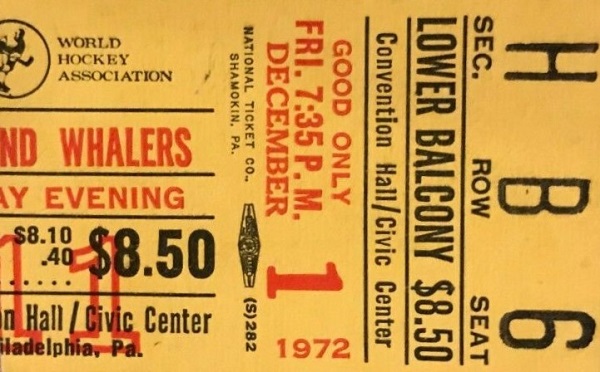

The Whalers first road game was to be the very next night as the back end of a home-and-home series against the Philadelphia Blazers at the Philadelphia Convention Hall. However, the game could

not be played.

Philadelphia Blazers Opening Game Ticket Stub

(courtesy of Tom Frost Collection)

In a rather comical Friday the 13th homecoming for the Blazers, the Zamboni literally crashed through the ice on its very first pass around the makeshift rink. In hopes that he would somehow calm

the restless fans, Philadelphia Mayor Frank Rizzo handed the microphone to the flamboyant Derek Sanderson to let the fans know that there would be no game.

Sanderson, never one to wax eloquent, proclaimed “Sorry fans. There will be no game tonight. I have no idea what is wrong with this ice. It is horrible and we can’t skate!” That wasn’t even the

worst part. The Blazers had presented all of the fans with commemorative orange hockey pucks to mark the special occasion, so the Philly fans, being Philly fans, started firing the pucks at

Sanderson, at the score board and anything else they could. Bing! Bang! Boom! In an instant, Sanderson had tossed the microphone and was running for cover to his locker-room.

That game would eventually be rescheduled and the Whalers would go on to have a very successful regular season splitting their home games between rinks, playing 20 games in the sticky floor and

smoke-filled confines of the Boston Garden and 19 games in the antique across town known as the Boston Arena. Even with half of the home games at the Boston Arena, with its limited seating, the

Whalers would lead the WHA in regular season attendance.

Boston truly was “Hockey Town” during this period and Boston fans just could not get enough hockey, and the Whalers were welcomed with open arms and a very faithful following. Fans that could not

find or afford tickets for the Bruins often attended Braves and Whalers games. With the WHA, they actually had an opportunity to see a game at the Garden and catch some well-recognized out-of-town

stars such as Bobby Hull and Gerry Cheevers.

The Whalers enjoyed their home ice advantage and would sit atop the WHA’s Eastern Division throughout the first half of the regular season led by the goal scoring of Tom Webster, Larry Pleau,

Tim Sheehy and the WHA’s Rookie of the Year Terry Caffery.

The experienced Whalers defense was equally stellar, playing a very physical brand of hockey in front of their talented goaltending duo of Smith and Landon.

The Whalers only made one significant trade during the season when they acquired left wing and former NHL Rookie of the Year, Brit Selby from the Quebec Nordiques by way of the Philadelphia Blazers

for Bob Brown as part of a three-team trade.

The season’s mid-point would have the Whalers sending six players to represent the Eastern Conference for the All Star game in Quebec on January 6, 1973. Players included Larry Pleau, Jim Dorey,

Tom Webster, Rick Ley, Terry Caffery and goalie Al Smith. Additionally, Jack Kelley was selected to be the Eastern Conference coach. The Eastern Conference won the game 6-2 with Whaler players Pleau,

Webster, Dorey and Caffrey all figuring into the game’s scoring.

The second half of the season had the Whalers battling with the Cleveland Crusaders to stay atop the Eastern Conference. The Whalers eventually held off the Crusaders and claimed the regular season

crown with the best record in the WHA at 46-30-2.

Finishing first overall proved quite valuable for the Whalers heading into the playoffs as they would have the home ice advantage throughout all three rounds. With all of their home games being played

in front of packed Boston Garden crowds, the Whalers would lead the league in attendance for the playoffs, as they had done during the regular season.

The opening round of the playoffs had the Whalers facing the Ottawa Nationals and the boys in green and white would win the series 4 games to 1 in a series that included two overtime wins.

Round two of the playoffs had the Whalers battling against the Cleveland Crusaders and, once again, the Whalers would win the playoff series 4 games to 1.

The third round of the playoffs, the Avco Cup Finals, showcased the two best teams in the WHA as the Whalers would face-off against Bobby Hull and the Winnipeg Jets.

The Whalers, not to be denied, knocked off the Jets in the series 4 games to 1.

The Game Five series finale was an exciting, nationally televised, high-scoring affair as the Whalers claimed the first WHA championship by a score of 9-6, which included a hattrick from Larry Pleau,

two more goals from Tom Webster and solid goaltending from Al Smith, who was in the net for the team’s 15th straight playoff game.

The Whalers had done it. Jack Kelley and the boys had captured the league’s first championship, and Ted Green would be presented with a trophy after the game. However, it would not be the Avco Cup as

that trophy never made an appearance at the Garden.

As Howard Baldwin would explain, “Game Five was scheduled for a Sunday afternoon and was to be televised on national television. As we were preparing for the game and possible championship presentation

on Saturday, we realized that the Avco Cup, if it even existed at the time, had not made its way to the Garden. Knowing that we could not have a championship presentation without a trophy, I sent

my VP of Marketing, Bill Barnes, out to go find something we could use. Barnes would make his way to a sporting goods store in Braintree, Mass. and come back with a big, fancy trophy made up that

said ‘Eastern Conference Champions’. Problem solved!”

So, it was this trophy, not the Avco Cup, that was presented to Ted Green, Jack Kelley, Howard Baldwin and the Whalers championship team on the Garden ice. For the players, coaches and management,

the trophy snafu was of no concern for them as they were super proud to cap-off their Cinderella season with the title as WHA Champions.

WHA's First Championship Trophy

(courtesy of Howard Baldwin)

Following the game, Baldwin issued a challenge to the NHL Stanley Cup champions, the Montreal Canadiens, to put the Cup on the line for a match-up between the two league champions. However, the Canadiens never responded to the challenge.

In my discussions with Howard Baldwin, Bruce Landon and Larry Pleau, each man was confident that the 1972-73 Whalers teams was as good as any NHL team at the time.

Larry Pleau explained “We were a very good team. We had talented forwards, strong defense, solid goaltending and we were tough.”

The Whaler's WHA Championship Ring

(courtesy of Howard Baldwin)

Over the league’s seven seasons, the Whalers would play their home games at the Boston Garden, the Boston Arena, the Springfield Civic Center, the Hartford Civic Center, and the Springfield

Exhibition Center before finally joining the NHL as the Hartford Whalers.

While the New England Whalers never won another league title, they will forever be remembered as the WHA’s first championship team.

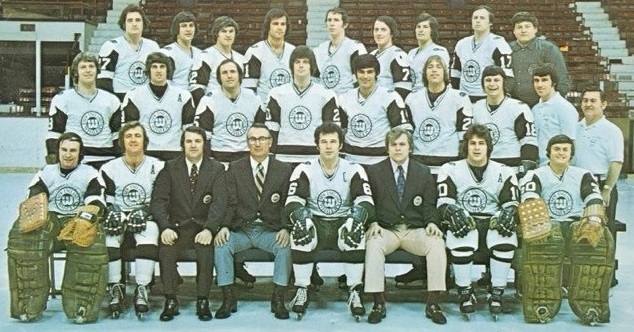

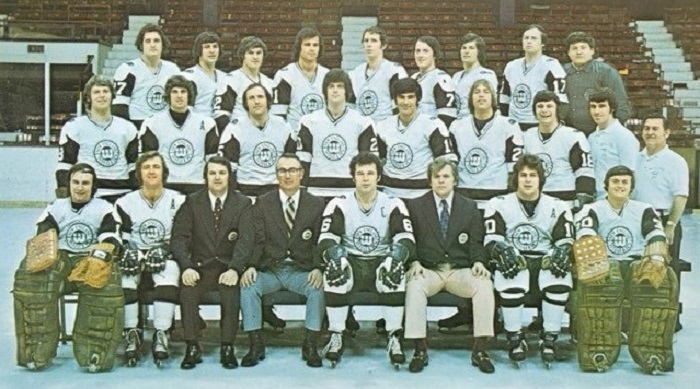

1972-73 New England Whalers

Front Row (left to right): Al Smith, Tommy Williams, Ron Ryan, Jack Kelley, Ted Green, Howard Baldwin, Jim Dorey, Bruce Landon

Middle Row (left to right): Brad Selwood, Larry Pleau, Paul Hurley, Ric Jordan, Tim Sheehy, Mike Hyndman, Brit Selby, Skip Cunningham, Joe Altott

Top Row (left to right): Tom Earl, Tom Webster, Rick Ley, John French, John Danby, Terry Caffery, Kevin Ahern, John Cunniff, Howard Hewitt

(courtesy of Mark Rankin)

References:

New England Whalers – 1972-73 Media Guide

“Slim and None” – Howard Baldwin

“The Rebel League” – Ed Willes

Acknowledgments:

I would like to extend my deepest appreciation to Whalers Founder and President Howard Baldwin and Whalers players Bruce Landon and Larry Pleau for being so gracious with their time and sharing

so many wonderful stories from their days with the Whalers.

I would also like to add a special “thank you” to my friend Keith Gentili and my amazing wife April Frost for their editing and proof-reading talents.